John the Baptist, fragment, Bronzino, Galleria Borghese

John the Baptist, fragment, Bronzino, Galleria Borghese

John the Baptist, Bronzino, Galleria Borghese

John the Baptist, Bronzino, J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, pic. Wikipedia

Portrait of Cosimo I de' Medici as Orpheus, Bronzino, Philadelphia Museum of Art, pic. Wikipedia

Giovanni di Medici as child, Galleria Uffizi (Florence), pic. Wikipedia

Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo and Her Son Giovanni, Bronzino, Galleria Uffizi (Florence), pic. Wikipedia

The muscular, beautiful, manly body with a delicately glowing skin seems to be taken out of a refined act of, as we would have said today, homoerotic nature, however, the title of the painting and the requisites visible on it, point to something completely different. This is a saint, and not just any saint – the patron of Florence, John the Baptist. But is it possible that this is simply a religious painting?

The muscular, beautiful, manly body with a delicately glowing skin seems to be taken out of a refined act of, as we would have said today, homoerotic nature, however, the title of the painting and the requisites visible on it, point to something completely different. This is a saint, and not just any saint – the patron of Florence, John the Baptist. But is it possible that this is simply a religious painting?

Attempting to find the answer to this question, we must stop for a moment at the author of his unusual work, the principal artist of the era of Mannerism and a favorite of the de’ Medici court – a painter and a poet with the nickname of Bronzino. This painting was created at the court of the Duke of Florence Cosimo I, in a period when the creator had already enjoyed well-grounded fame and the position of the court painter. He found renown mainly as an author of sublime, dignified courtly portraits, and multi-figure religious compositions. In the former, he was able to capture a sort of haughtiness combining at the same time naturalism with idealization. The images of the portrayed – mainly members of the de’ Medici family – strike us with their subtle elegance of proportions and slim bodies with a noble expression of elongated faces. Bronzino was also able to splendidly express the refined beauty of their robes, shining armors, expensive brocades, and silks, but at the same time, the nude bodies he painted could have seemed like a matter of sublime, ideally pure and smooth tissue. His religious paintings, on the other hand, are characterized by excellent composition, hieratic immobility, subjecting the color to the drawing, and a large dose of courtliness. And this is also the case with St. John the Baptist.

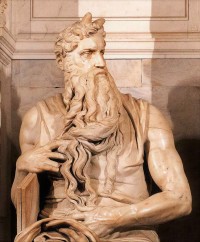

On a ledge, among rocks, which are in some parts covered with ivy, sits a young, naked man (John the Baptist), who looks upon us with a ruling glance. In one hand he is holding a bowl with water (baptismal) – his attribute, with the other he is leaning on the edge of a body of water with a spouting spring. Behind the prophet, we can see another attribute of his – a lying, thin cross. No emotion can be found upon the youth’s face, he is simply motionless in a studied pose. The unnaturally red lips, rosy cheeks, and curly red hair, additionally strengthen the effect of artificiality, even theatricality of the figure. He himself – beautiful, without a blemish – seems to be more sculpture than flesh. This is further highlighted by a piece of fur covering his shoulder, which the artist painted with such precision that we can almost feel its warmth and softness. However, it does nothing to warm the body frozen in stone. Strangely, that which is alive seems to be less natural than the skin of a killed animal. The distinct, almost incredible naturalism is mixed in the painting with an icy, bordering on exaggeration, precision. The body of the youth becomes a valuable stone, thanks to the pallet of cold colors, the artist transforms it into a kind of refined incrustation.

However, despite that fact it emanates eroticism, while the complicated twist of the body seems to underline this fact. It should come as no surprise that many of the historians who studied the painting, focused on pointing out the fashionable at that time in the literary and artistic community of the Florence elites homoerotic aspects. They appeared in aristocratic culture, not only in the city on the Arno, but in all of the courtly Europe of the Renaissance period, mainly in literature and poetry. The excitation of "sin against nature" perfectly fits with Mannerism and its strive for exaggeration, refinery, extravagance, and spiciness, as well as the desire to of subtlety, virtuosity, and stylization. But is it possible to draw such far-fetched hypotheses when it comes to the court of Florence, known for its rigorous Catholicism, nurtured under the watchful gaze of the religious Eleonora of Toledo – the principal patron of the painter and the person for whom the work was painted? Let us not forget, that we find ourselves in a period of admiration (especially in Florence) for the works of Michelangelo. Bronzino also thought very highly of him and it was from him that he borrowed the incredible twist of the body of John the Baptist, from one of the Slaves. For the divine Michelangelo, the human body was the perfect object of creative searching; it is enough to take a look at his young men painted on the vault of the Sistine Chapel. Furthermore, he was known for his (albeit concealed) love of beautiful boys, which had absolutely no influence on the perception of his work. Therefore, we are talking about a community open to the poetry of Petrarca and to the newly discovered Greek philosophy with its apotheosis of love towards youths-students, while on the other hand of a society in which that which remained unnamed and unsaid (homosexual), did not exist. For the former religion was in complete opposition with erotic preferences, for the latter homoeroticism was simply a sin, which could be forgiven if one was wealthy and influential.

While the time of adoration of the art of Michelangelo had not yet passed in Florence, the Church treated nudity, much differently in the middle of the XVI century than in the previous decades. It was no accident that Pope Paul IV ordered the nude figures of the Last Judgement to be clothed. Now, at the time of the Counterreformation, the nudity of a man’s body was only acceptable in two cases – to a limited degree in paintings of religious nature, and surprisingly enough, in portraits. We know a number of Bronzino’s paintings, in which he portrays the rich and famous of that time as mythological figures (Andrea Doria as Neptune, Cosimo I as Orpheus). In the painting, we are presently discussing we see John the Baptist as a figure, which next to Saint Sebastian, for centuries, had given artists a pretext to represent beautiful, nude, manly bodies. According to historians, we are dealing with, not so much, an image of St. John the Baptist, but with his namesake, the freshly ordained archbishop of Pisa and cardinal of the Roman Church of Santa Maria Domnica – Giovanni Cosimo de’ Medici, the second son of Duke Cosimo I and Eleonora of Toledo. He was destined to become a clergyman, as was planned by his father. We are familiar with the moving childhood portraits of this boy; here Giovanni is shown as a seventeen-year-old youth, with a visible resemblance to his father – the same curly, slightly red hair, regular facial features. It must be admitted, that Bronzino’s predilection for youths with curly, red hair is immense indeed. We can see them in many of his paintings.

Giovanni de’ Medici died of malaria (1562), one year after his work had been completed, similarly to his mother. His father’s and family’s great ambitions, which saw in him a future pope, had come to nothing.

Today the fame of Bronzino – an outstanding representative of the refined Florentine culture of the middle XVI century has somewhat faded, however his works, including this very act, had not lost its attractive, ambivalent aura. Its foundation is characteristical for the Mannerist search for a style that is thoroughly subtle. The topic does not matter, only the method of its articulation is important – be it in words, or through the creation of difficult to understand conceptual puns, which is true for both literature and courtly painting of those times. And in this painting, the border between charm and affectation is completely lost.

It is difficult to say whether it was the style, or the admiration of the beauty of a youthful body, for which Cardinal Scipione Borghese was known, was the principal reason for his buying of Bronzino's painting for his Roman collection. We do, however, know that this was one of the first works in the collection of the famous patron of the arts.

Saint John the Baptist, Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano Tori), approx. 1560-1561, oil on wood, 120 x 92 cm, Galleria Borghese

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !